Up until 1542, the whole of Ireland was an English lordship, it was controlled by the King of England as ‘Lord of Ireland’. In 1542, King Henry VIII established the Kingom of Ireland.

MIn the early 17th century, the conquest of Ireland was complete. Land was confiscated from native Irish Catholics and it was colonised by Protestant settlers from Britain. Most catholics did not recognise Protestant monarchs and continued to support the Jacobite government-in-exile from 1688 onwards.

During most of the history of the Kingdom, catholics got a raw deal. Catholicism was suppressed, they were barred from government, parliament, the military, and most public offices. In the 1780s, the parliament gained some independence from Britain, and some anti-catholic laws were lifted. In 1801, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Parliament of the United Kingdom were created. This meant the abolishment of the Irish parliament and giving Ireland representation in the British parliament.

In the 1840s, there was the Great Famine, where potato blight led to mass starvation and a significant decline in population. Following this, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a campaign for Home Rule gained momentum. The campaign was for Irish Independence but it faced strong opposition from unionists, especially in Ulster (one of the 4 traditional provicines of Ireland and comprised of 9, or 6, counties depending on who you talk to). The Fenian Botherhood was set up in the 1850s and was active in Ireland, USA and Britian, with the goal of achieving Irish Independence from British rule. They organised a major rebellion in Ireland in 1867, but it was ultimately unsuccessful. They legally disbanded in 1880. The term ‘Fenian’ evolved to become a derogatory term for Irish Catholics in a sectarian context.

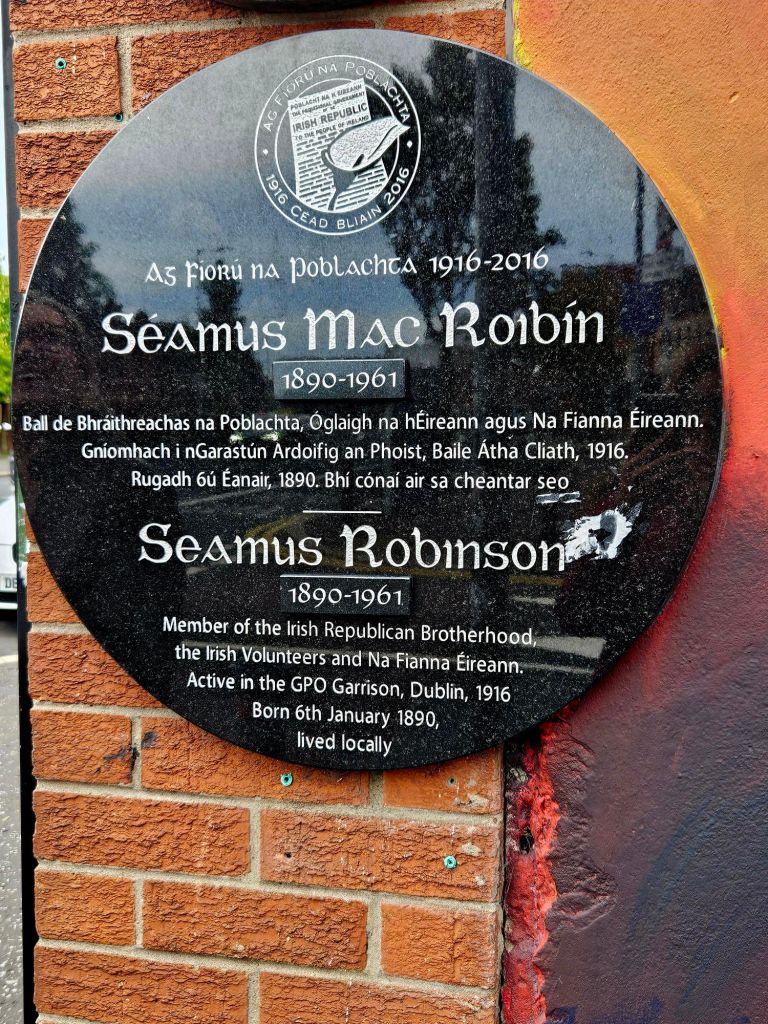

In 1916, the Easter Rising was launched by the Irish republicans against British Rule and was the first armed conflict of the Irish Revolutionary period. Sixteen of the Rising’s leaders were executed, leading to an increase in support for Irish Independence. This was demonstrated when Sinn Fein won 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the 1918 general election.

Northern and Southern Ireland split in 1921, established by the Government of Ireland Act 1920 and formalised by the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. This partition created Northern Ireland, which remains part of the UK and the Irish Free State, the Republic of Ireland. This meant Northern Ireland remained part of the UK, with its own devolved government in Belfast.

From the 1960s to 1998, there was a period of political and sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland referred to as The Troubles. It began in the late 1960s as a civil rights movement by Catholics against the Protestant dominated government’s suppression of peaceful protest, such as the 1968 Derry /Londonderry protest. It triggered escalating clashes between loyalists (who were mainly protestants) and those seeking independence (who were mainly catholic) as well as the police. By the summer of 1969, widespread rioting erupted, leading to the deployment of British troops and the start of the very long conflict. The primary driver was the systematic discrimination against the Catholic minority by the Protestant dominated NI government.

And so at 3pm we met up with our taxi driver, Stevie, who was going to take us on a history tour of Belfast. Stevie had quite a strong accent, so you had to really listen to what he said.

Just outside of the city are Falls Road and Shankill road, which are where a lot of the fighting happened during the Troubles. They still have huge barricades up between the protestant and catholic areas. These barricades have gates that close at 8:30pm on weekdays and 6:30m on weekends. The barricades stop the two sides mixing, but both sides can still get into the city of Belfast and back. Within Belfast, there are around 60 Peace walls, community dividing barriers. Many were built during the Troubles, but some have been added since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

Up until the late 1960s, catholics were unable to vote as the voting system was based on how many properties you owned and whether you paid tax. This meant that voting was heavily weighted in favour of the protestant community as they owned the properties. This resulted in many towns and cities with a catholic majority still being unionist-controlled.

Even today, over 90% of children attend segregated schools.

There are 5 walls between the Shankill and Falls Road areas. Most of the gates are closed manually every evening, but one is closed remotely. All are monitored 24/7.

Although the Troubles finished 27 years ago, the protestants and catholics want the walls to remain as they make them feel safe. Some of the walls go right through people’s back gardens, and some of the houses also have a protective layer.

The bottom part of the barricades were built in 1970s and are bomb proof. The next section was built in the 1980s to add more protection, and the final top section in the 1990s to stop bottles and other items being thrown over.

Even before the British Army arrived in 1969, people had already started to build the barricades between the two sides. Children were told to never cross the barricades and became afraid to do so.

In the catholic areas, the road signs display the name of the road in both English and Irish. In the protestant areas, only the English name is displayed. As you drive down Shankill Road and the protestant area, it almost feels more patriotic than England itself, with banners and red, white and blue kerbs.

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) was formed in 1971 to defend the unionist communities during the Troubles. Initially, they were unarmed. Over time, they became a criminal and sectarian gang responsible for many deaths. They used the cover name Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) to claim responsibilities for the violence and avoid political issues. The UDA was banned (declared illegal by the British government) in 1992 and the UFF in 1973. The UDA does still exist, but they have agreed to a ceasefire.

We saw a large mural in the protestant area dedicated to Stevie McKeag, declared Top Gun. This is because he had killed the most catholics. The eyes of the snipers on the mural followed you wherever you went. This mural is illegal and should be removed by the local council, but the members of the council are supportive of the unionists.

Poppies are also painted on this mural. Red poppies are not worn by the catholics.

Throughout the Troubles, women’s voices were not listened to. Just down the road from the Stevie McKeag mural is one that is a lot more positive, providing a message of change and unity, bought together by the Lower Shankill Women’s Group.

The unionists (protestants) believe that the province of Ulster has 6 counties, whereas the republicans (catholics) believe it has 9. This is because 6 of the counties are in Northern Ireland, and 3 are in the Republic of Ireland.

During the troubles, there was always a lot of noise, and people got used to it. Since the ceasefire, people have had to adapt and get used to the quiet.

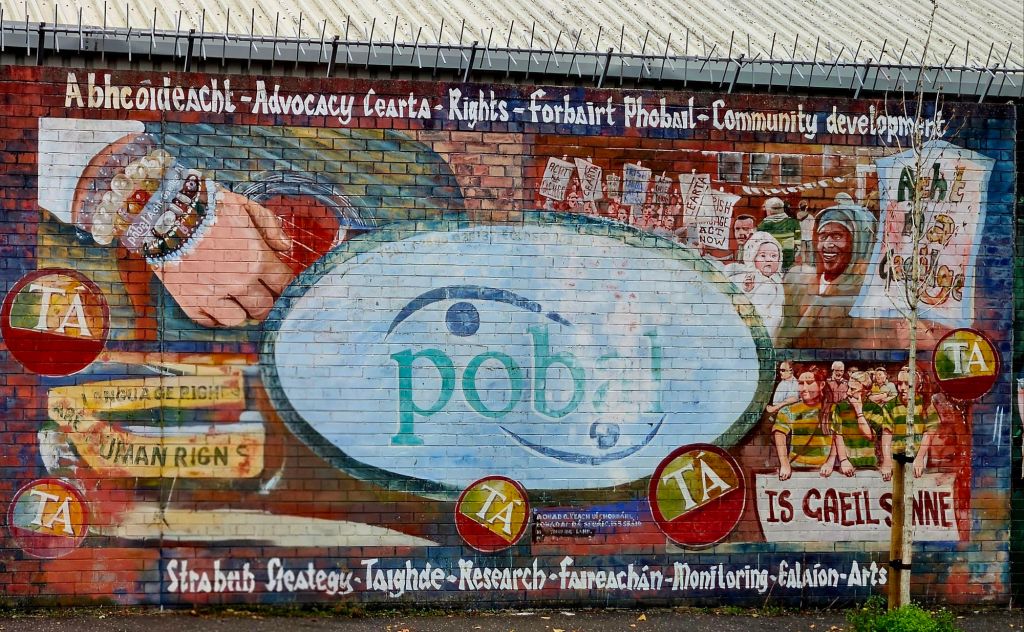

We then went to the International Wall, which is a specific 48m section of one of the Peace Walls in Belfast. This part of the wall serves mainly as a large public gallery for murals on social justice and international solidarity. It has become a symbol of hope.

We then went to another section of a Peace Wall, which we were able to add pur signature to. The oeace walls stretch over 34 km (21 miles), and some are around 8m tall. They can be made from a combination of brick, iron and steel. Over 3 500 people died during the Troubles, with almost 70% of deaths happening within 50m of one of these walls.

We then went to the Catholic area of Falls Road. The first place we visited was the Clonard Martyrs Memorial Garden. You could tell we were in a Catholic area as the Flag of Ulster was on display – a red cross on a yellow field with a red hand of Ulster).

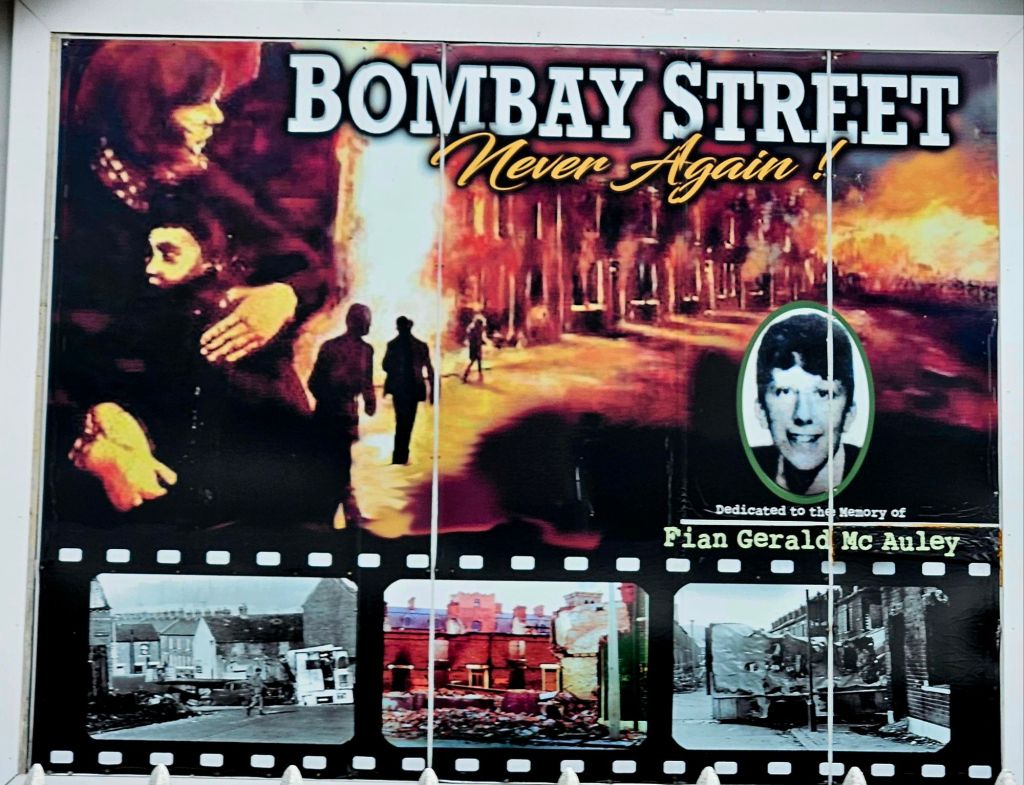

This memorial on Bombay street is to remember those individuals from the community who were killed in the conflict. In 1969, loyalists attacked the street and burnt down most of the homes and it is this even that is often cited as the start of the Troubles. Within 2 weeks of the Troubles starting, 50,000 people were displaced from their homes. The homes in this area were rebuilt in the 1970s.

Our driver told us the story of Nora McCabe. Nora was killed by a plastic bullet on the Falls Road in July 1981. She was only 33 years old, a mother of three, and was killed by a police officer from the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which existed in Northern Ireland between 1922 and 2001. The police originally stated that serious rioting was taking place at the time, which was they fired, but this was later disproven. A French Canadian journalist happened to film the incident where Nora was shot in the head with a plastic bullet. She died in hospital 36 hours later. Despite this evidence, nobody was ever prosecuted for her death. The police were only supposed to shoot these bullets below the knee, and they have only ever been used in Northern Ireland and South Africa. 17 people were killed by plastic bullets in Northern Ireland.

I always thought plastic bullets were the same size as a normal bullet, but they are huge – Faye is holding a plastic bullet and rubber bullet in the photo below.

In 1971, the British government introduced interment without trial. This meant that suspected members of paramilitary groups, such as the IRA, could be retained without a trial. Many innocent people were detained in this way, causing more unrest and more support for the IRA. The policy remained in force until 1975.

Convicted paramilitary prisoners were treated as ordinary criminals until 1972, when a Special Category Status was introduced. This meant prisoners were treated like prisoners of war, they didn’t have to wear prison uniforms or undertake prison work. In 1976, the British government stopped the Special Category Status for paramilitary prisoners in Northern Ireland. The IRA viewed this as a threat to their authority and responded with violence, including the assassination of prison officers.

The prisoners refused to wear the prison uniform, so they used to go out and exercise just covered in a blanket. This became known as the Blanket Protest. Because the prisoners refused to wear a uniform, they also couldn’t receive visitors.

The protest escalated to a point where prisoners were smashing the furniture in their cells, so all furniture was removed, and they were left with blankets and a mattress. Prisoners refused to leave their cells so they were unable to be cleaned, and this became the ‘dirty protest,’ where prisoners smeared their excrement on the walls. In 1980, seven prisoners went on hunger strike, asking for 5 demands; the right not to wear a prison uniform, the right not to do prison work,the right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits, the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week and full restoration of remission lost through the protest. This hunger strike lasted 53 days, but the promises were not fulfilled by the British government.

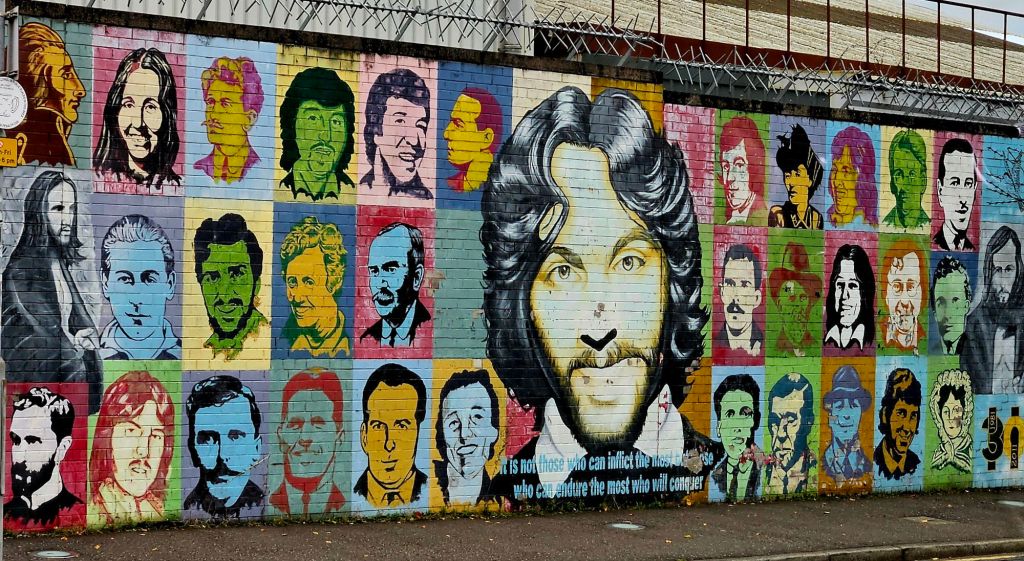

In March 1981, a further hunger strike began with Bobby Sands and resulted in the death of 10 prisoners. This hunger strike ended in October 1981 and resulted in a change in prison policy.

Bobby was a member of the IRA and was sentenced to 14 years in prison. He was only 27 when he died. Sands started the hunger strike, and other prisoners joined at staggered intervals to maximise publicity, with prisoners steadily deteriorating over several months. Shortly after the start of the hunger strike, a sudden vacancy became available for a seat with a nationalist majority. Sands stood for the seat and won it on 9 April 1981 whilst in prison. He became the youngest MP at the time. He died less than a month later without ever having taken his seat in the Commons. Bobby Sands survived 66 days on hunger strike.

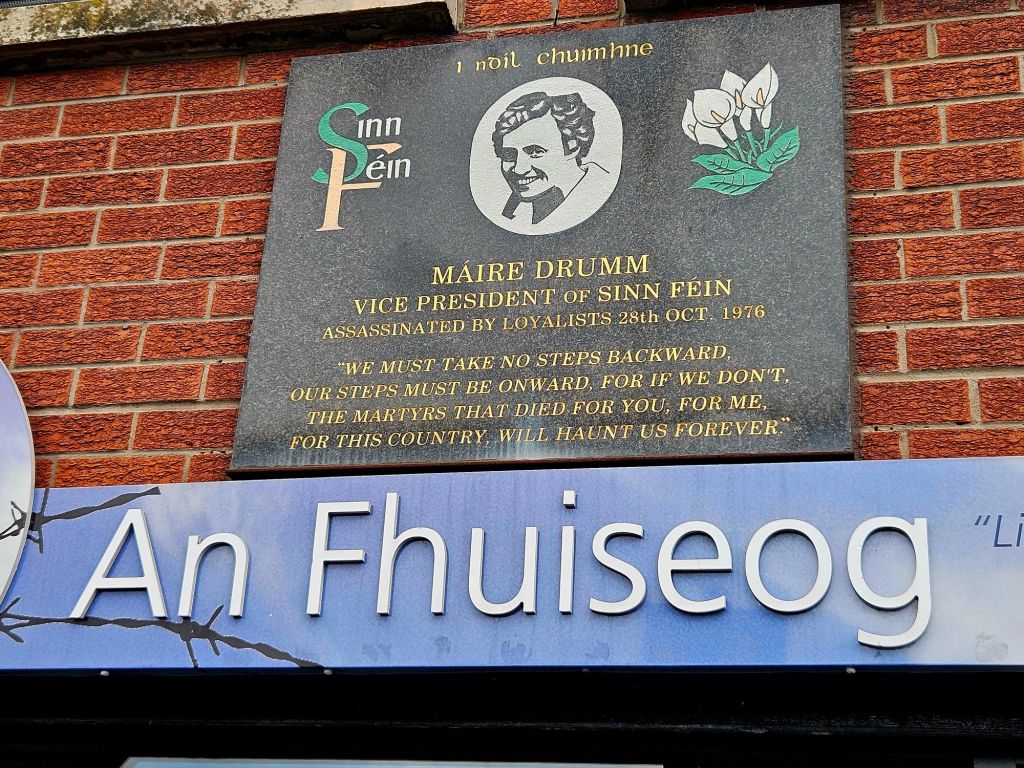

We then came across a Sinn Fein office. Sinn Fein means ‘we ourselves’ and was regarded as the political wing of the IRA, although they are now seen as separate organisations. The party was led by Gerry Adam’s from 1983 to 2018. Sinn Fein began back in 1902 but was of little importance until the Eater Uprising in 1916. In 1918, they won 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the British parliament.

In 1969, the party split into two over whether to use violence to protect the Catholics in Northern Ireland. They became known as the ‘workers’ party’ who were against violence and the provisional party. Sinn Fein was banned in the UK until 1974 as many of its leaders were thought to be members of the IRA. Up until 1981, members of Sinn Fein, who had acquired council seats, didn’t attend meetings as a form of protest against British rule. Sinn Fein, under the leadership of Gerry Adam’s and Martin McGuiness, agreed the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Sinn Fein continues its policy of abstentionism at Westminster, where it has 7 of Northern Irelands seats.

This was the end of a very interesting black taxi tour. Many innocent people were killed on both sides of the Troubles, and it will be a while before the two will be able to live without the peace walls separating them.

As they say, oppression breeds resistance.